Site, Style, SelectionTM is a simple three-step process that successful gardeners use to help ensure gardening success. Even if you have little or no experience as a gardener, this simple system will get you off on the right path.

So how does this system work?

Easy as one, two, three!

STEP ONE: UNDERSTAND YOUR GARDEN SITE

To understand your site you need to perform a site analysis. You will be the detective, gathering data about your site to find out which garden options should work on your site. Site analysis doesn’t take much effort, yet it is the most important thing you can do to prepare for a garden.

The first step is to understand all the conditions that affect your garden site – climate, soil, sun, and specific conditions. These contributing factors will be the foundation for building the rest of your garden.

Climate:

Understand your regional climate, area climate, and microclimate.

The regional climate, or at least the regional temperature range, can be determined by referring to the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map in the “Toolbox” area of the Garden Tutor site. Zones are based on average monthly minimum temperatures, so just know what zone your site is in and choose plants that grow in your zone, especially if you order plants by mail. If you purchase plants from local nurseries, chances are good they will grow in your zone, although there are exceptions.

Your area climate is the general area surrounding your site. It includes your town, city, or county. Nearby hills and valleys, large bodies of water, and large metropolitan areas can affect all manner of weather factors. It is then a more accurate measure of what will constrain your gardening decisions than the regional climate because it encompasses a much smaller area. It is important to note that area climates can be subject to other influences beyond weather, such as common soil types or deep valleys that get reduced amounts of sunlight. To determine your area climate, watch local weather reports for trends, and pay attention to general descriptions that people use when discussing your area. Descriptions like “the soil in our area is very acidic” or “our weather is affected locally by the wind patterns off Lake Erie” can clue you in to the prevailing conditions in your area. You can also ask your local nursery staff or talk to your gardening friends.

Your microclimate includes all of the conditions specific to your site, and it is your most important gardening constraint. Your microclimate is made up of soil, sun, and specific conditions we will outline each of them in more detail here.

Soil:

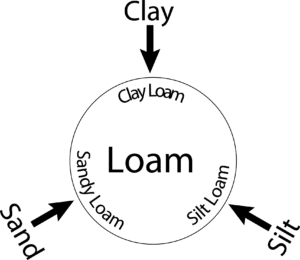

Determine your soil texture, structure, pH, and nutrients. The ideal garden soil is the one that best suits the needs of your plants. Although some plants prefer more extreme soil conditions, the best soil for most plants will be one that has a loamy texture, good granular structure, a 6.5 pH, and plenty of organic matter. Our Garden Tutor pH strips are an easy way to help determine the pH of your soil – Available on Amazon here! so you can quickly get your pH optimized with little effort. Soil pH impacts nutrient availability, and a 6.5 pH is optimal for most plants. For a more in-depth nutritional analysis of your soil, consider getting a laboratory soil analysis performed at a soil testing lab. We have assembled a list of soil testing labs here

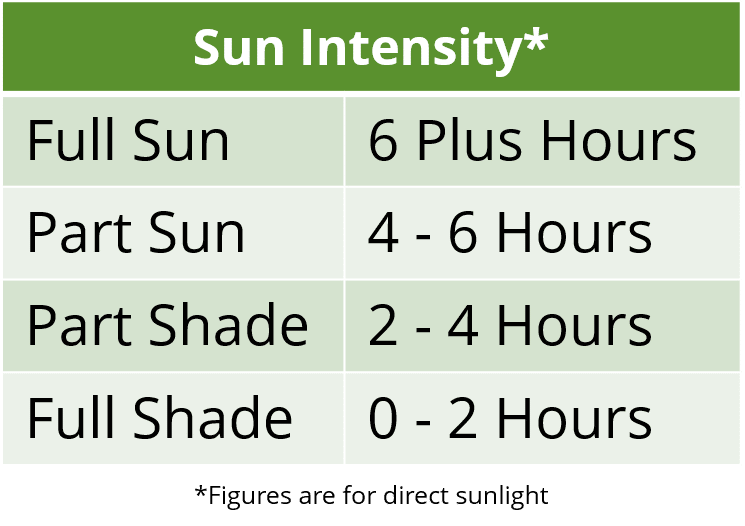

Sun:

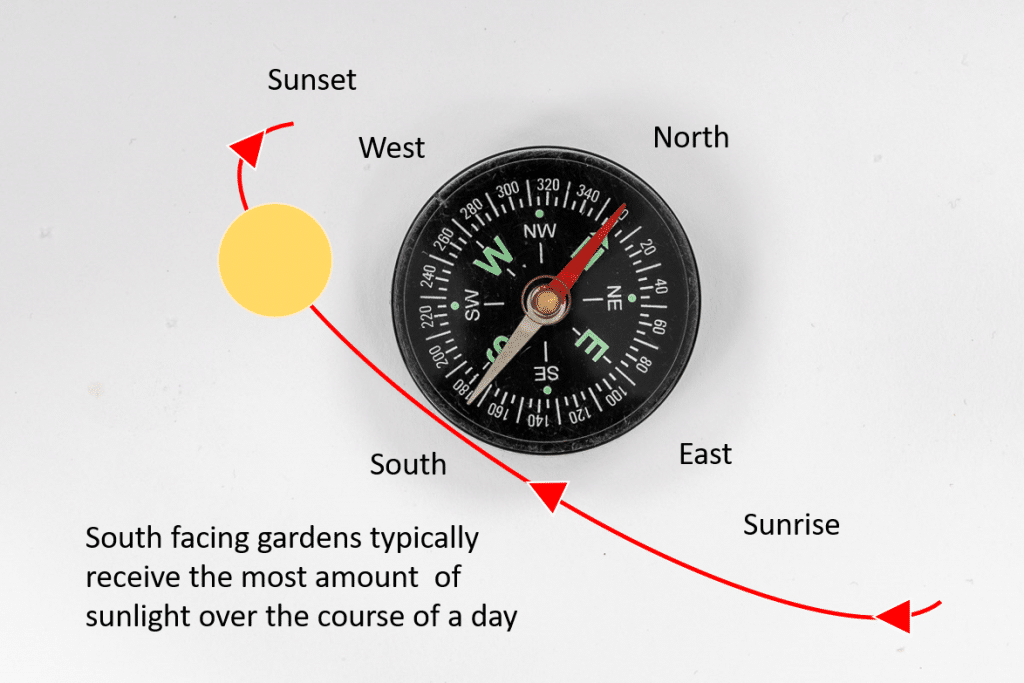

Adequate sunlight for plants is essential, if they don’t get the sunlight they need they simply will not grow well. There are two things about the sun you need to know for your site analysis: the path and amount.

Determine how many hours of direct sunlight your garden site receives over the course of a day and how this path will change over the year, depending on your location. The first step is to get a compass. Yes, like the kind you used in boy/girl scouts or at summer camp! Sounds silly, but you will be surprised. You may think you have a rough idea of East and West, but a compass will give you a much more accurate reading. We provide further details in the “toolbox” section of the Garden Tutor site on how to use a compass and even how to plot the exact amount of sun your garden site receives.

Specific conditions:

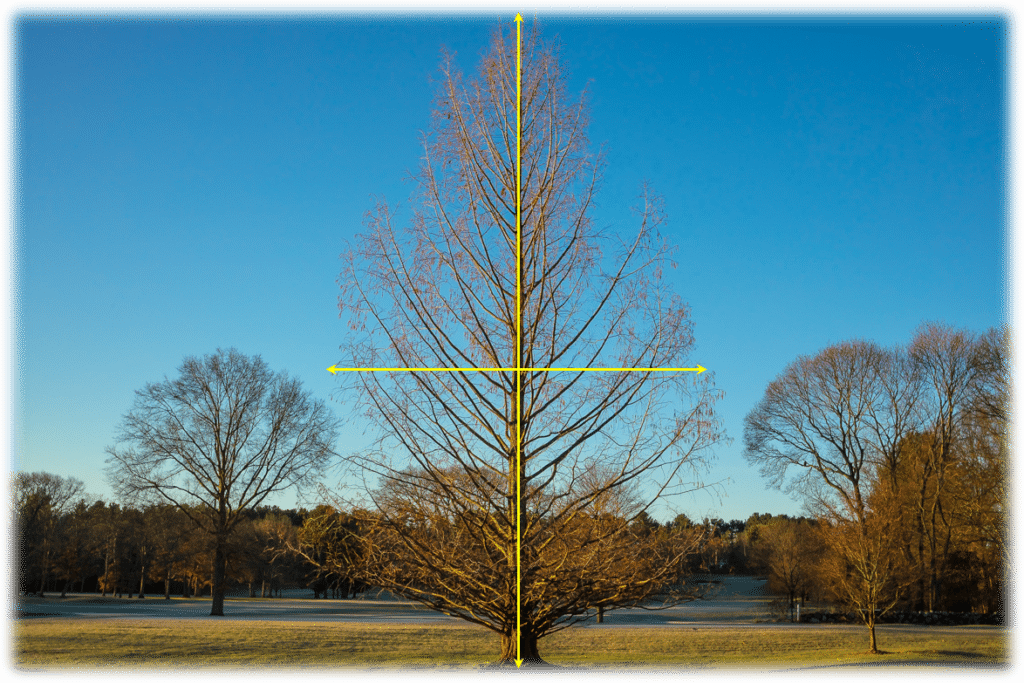

These are conditions specific to your site and are made up of wind (prevailing wind patterns and inconsistent wind patterns), structure (trees, houses, buildings, fences, etc.) and variables (factors that may or may not affect your site like underground utilities, salt or dealing with animals).

STEP TWO: DEVELOP A STYLE

The next step is to develop a garden style. The critical aspects of creating a garden with style involve –

- Scale: The relative sizes and distances of objects in the landscape to each other and the viewer. You want to try to keep things in proportion. Some people refer to the “golden rule” as a way of helping you maintain proportion in the garden. The rule is basically that beds and borders, lawns, and structures should be at about a 1:1.6 ratio. So a bed that is 10 feet wide should 16 feet long. That size “feels “right because it is in sync with proportions found all around us in nature. In any case, scale is hard to master, and you typically have constraints. Do your best, and you can’t go wrong.

- Symmetry: In general, symmetry involves mirror-imaging: items are symmetrical if their parts are uniformly balanced and spaced on each side of a dividing line. In gardening, symmetry implies formality, and asymmetry implies informality.

- Simplicity: Simplicity when designing can be good. While you don’t want to overdo it, deliberate spacing, uncluttered beds, repetition of plants, and simple lines can enhance your garden and make it easy for the viewer to appreciate it. It also helps the viewer discern subtle changes in style as they are led through the garden.

- Variety: A garden with a broad assortment of plants and arrangements can be a genuine delight. A variety of different plants can open new doors to contrast and beauty. After you have decided on a theme and style for your garden, try to select a variety of plant shapes and sizes that fit your theme and your site constraints. You don’t want to overdo it, though. Keep your design simple, but remember that variety can be the spice of your garden.

- Arrangement: Beds and borders, lines and curves, plants (specimen planting, grouping or massing), texture, and color. All of these things are the tools you will use to bring order to your garden. The arrangement is the way you frame and organize your garden. Arrangements can be simple or complex and layered. This is the fun part, and the more plants and combinations you learn about, the more creative you can be.

STEP THREE: SELECT YOUR PLANTS

Select plants that are well suited to your site and garden style. The secret to plant selection is choosing plants after you understand your garden site and have a garden-style in mind. Plants are the building materials for your garden. And like a house, you first want to make sure it’s appropriately situated on your property and that you have a working design in place before you start building. The same applies to gardening. Most of the time (but not always), you want to select the plant material after you know your site constraints and have a design in mind.

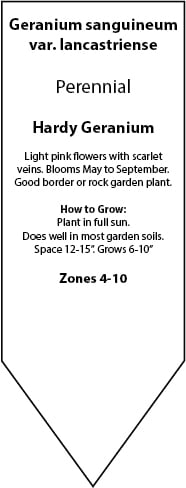

Nursery stock should be labeled. A good label will tell you the basics: how and when to plant, proper spacing, and the plant’s hardiness zone. It should also list any special features that the plant has, such as its color, texture, or size.

The following is a brief description of the significant plant categories that you will come across at the nursery. At the most general level, plants break down into two groups: woody and non-woody plants. Note that some plants can be listed separately from theses basic categories, either because they are trendy or because they have distinctive characteristics that they have become known by. Some of these plants are roses, herbs, vegetables, edible berries, groundcovers, shade plants, and vines.

Woody Plants

- Deciduous Trees and Shrubs – Woody plants that lose their leaves at the end of the growing season are deciduous. Some offer dazzling floral displays before most other plants emerge in the Spring. Many deciduous shrubs bloom at other times of the growing season, so you can choose them based on their bloom period to fill gaps when many other plants are past their blooms. Some deciduous shrubs have interesting foliage and/or bark, so you can choose them for texture contrasts as well.

- Semi-evergreen Trees and Shrubs –These are plants that may or may not lose their leaves, depending on your climate. In many instances, there are trees or shrubs that are usually deciduous but in southern climates are truly evergreen.

- Evergreen Trees and Shrubs – Shrubs that do not lose their leaves count as evergreens. These include broad-leafed, narrow-leafed, and needled evergreens. They are good to have in wintry climates.

Non-Woody

- Annuals – Annuals live for only one growing season. They bloom profusely throughout the growing season and usually last until the first major frost in your area. You will have to replace them annually, hence the name. They are primarily chosen for their flowers but in some cases for their foliage color and texture, because they provide continuous color throughout their growing season. They are most effective when massed or grouped.

- Biennials – These are good bloomers (usually not as good as annuals) that generally live for two growing seasons and then die. They spend their first year maturing, and may not produce any flowers. During the second season, they will bloom for extended periods. Often they will self-seed, so you may not have to buy replacements. They are effective when massed or tightly grouped since the flowers are their primary aesthetic attributes.

-

Biennials in bloom Perennials – These plants endure year after year, lying dormant during the winter months and reappearing in the spring. They usually have a limited (1-4 week) flowering period but are widely used because they don’t require frequent replacement, and their blooms can be quite spectacular. Since perennials rarely maintain blooms throughout the growing season, you should focus on their shape, texture, and foliage color, as well as their flowers. Massing and grouping are common arrangements.

- Bulbs – Like perennials, bulbs bloom for a short time during the growing season and then go dormant by the end of the growing season. Unlike perennials, bulbs can survive (when dormant) for extended periods without soil or water. Bulbs are usually chosen for their blooms and generally are used to compliment an existing, longer-lasting floral display. Spring bulbs (so-called ‘hardy’ or ‘true’ bulbs) bloom while your other plants are maturing, thus giving you some early garden cheer. Bulbs are either massed, tightly grouped, or naturalized by scattering them and planting them where they fall.

- Succulents – These include Cacti and other plants that store water in their leaves or stems. They generally prefer desert or tropical sites, although some adapt well to cooler climates and are sometimes lumped in with perennials at nurseries. They require little water and generally like full sun conditions. Specimen planting, grouping, and massing are all good choices for planting succulents, depending on their size, shape, and habit.

So there you have it — three steps to garden mastery. If you want to learn more, take our FREE introductory Garden Tutor course and order the integrated course kit. For the cost of a medium-sized shrub, you will learn how to be a confident and competent gardener.

Good luck, and we hope to hear from you soon!